Headlines are crafted with a goal of grabbing your attention. They are designed to get you to buy, click, or react. And they often do this not by focusing on topics that engage the areas of your brain responsible for logic and reason, but rather the more primal elements of greed and fear. Even armed with that knowledge, their siren song is hard to resist.

Take for example the widely discussed financial topic of the moment—inflation. Reading headlines like, “The Specter of Inflation” 1 or “Inflation: A high price to pay” 2 or “Get Ready for Inflation and Higher Interest Rates: The unprecedented expansion of the money supply could make the ’70s look benign” 3 are sure to make you feel uneasy and question how you’re prepared for the “inevitable.”

Reading further into the story that follows the last headline, written by a prominent economist and published in The Wall Street Journal, we see, “It’s difficult to estimate the magnitude of the inflationary and interest-rate consequences of the Fed’s actions … To date what’s happened is potentially far more inflationary than were the monetary policies of the 1970s, when the prime interest rate peaked at 21.5% and inflation peaked in the low double digits.” 3 With such a strongly worded argument penned by an expert, how could you not raise up and want to take action to either protect yourself or try to take advantage of the impending disruption? Do your feelings change to know that the first two headlines are from 2011, and the last headline is from June 2009, and that monthly inflation numbers over the past 12 years average an annualized 1.7%? 4

Today's Inflation Fears

The fear of hyperinflation coming out of the global financial crisis was omnipresent for years due to the unprecedented actions taken by the government and Federal Reserve to keep the banking sector and economy from further collapse. The story of today’s fear is very similar. Trillions of dollars in pandemic relief have entered the market, and the concern is that prices will have to rise. Some of these fears are being stoked by actual price increases, though it’s too soon to say whether these spikes will be transitory in nature due to short term supply chain disruption and lack of production or potentially more permanently elevated prices.

So, why were the economists and inflation hawks warning us of peril in 2009 so wrong? And in that context, how should the current inflationary fears be viewed? The short answer is that accurately predicting future inflation is nearly impossible. And those lucky few who may get it right in one instance are unlikely to get it right the next time.

Even in hindsight, economists often come to different conclusions on what caused, or didn’t cause, inflation to spike over time. The challenge with predicting the future is that it’s always different than the past, and, therefore, building models and applying the lessons of the past to future scenarios may lead us to draw incorrect conclusions about cause and effect.

A Brief History of Inflation

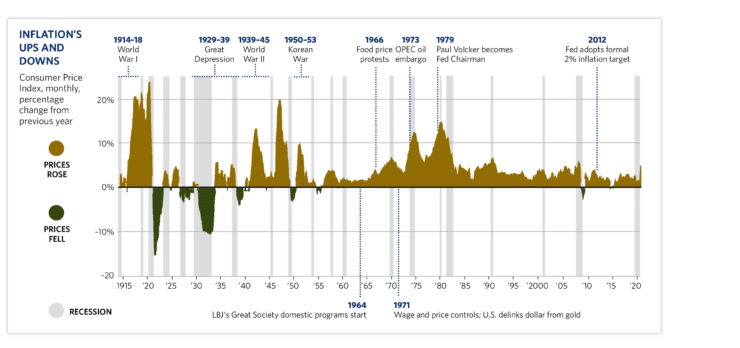

When looking back over our relatively short economic history, we see wildly different experiences in inflation in the first 70 years compared to the past 35. This may lead some to conclude that we’re due for an inflationary spike. It may cause others to conclude that the earlier period isn’t helpful for today’s globally connected world. The most dramatic inflationary spikes that we see in the chart above are related to production and supply shortages during world wars and economic growth that occurred when the dust settled on these dark periods—events that we cannot plan for in structuring investments within a long-term portfolio. The prolonged inflationary period of the 1970s and early 1980s included markets processing the delinking of the U.S. dollar from the gold standard and energy shortages stemming from the OPEC oil embargo—events that may not pose a risk to repeat in the future. Additionally, the Federal Reserve is very different today than it was in these periods. In the past 20 years, there has been a clear demonstration of an increased role of the Fed to support economic growth. Depending on your point of view, this may be a good thing or a bad thing, but we shouldn’t expect a return to a hands-off Fed any time soon.

Strategies to Protect From Inflation

So, with all that said, what can we do about inflation if it does rear its ugly head? One of the first thoughts that people often have is to include gold in their portfolio to protect against a potential decline in the value of the U.S. dollar during inflationary periods. This conclusion is typically supported by the experience of the price of gold during the inflation of the 1970s, during which gold far outpaced the rate of inflation and other traditional hedges. However, when we play that story forward, we see that gold has not kept up with inflation since its highs of 1980, and it has had decades-long periods in which it lost value.

In a similar and more modern theme, Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies have been referred to as “digital gold.” But beware, they continue to be extremely volatile, with daily price movements that can dwarf a decade’s worth of inflation. Additionally, although accessing many cryptocurrencies is becoming easier with some custodial platforms allowing them to be bought and sold directly or though intermediary vehicles, the implicit and explicit fees associated with these trades can be many percentage points of the traded value.

Given that inflation is a measure of the price change of goods and services, buying the raw components of the “goods” through a basket of commodities should certainly be an inflation hedge, right? Sadly, no. There are many challenges with commodities if you’re trying to hedge against inflation. One is that they don’t cover the services side of inflation well, and with our economy and many expenses tied to this half of the equation, we may not actually be tracking experienced inflation. A second challenge is easy to see when reviewing their returns of over the past 15 years—a time in which a broad basket of commodities lost value half the time and ended with a return of -4% per year with volatility higher than the S&P 500, which gained 9.9% per year. 5 And although this year has been a great time to invest in commodities like oil, steel, and timber due to massive price increases from pandemic-related supply chain shortages and a reopening of our economy, we have already started to see some prices fall sharply, with lumber down well over 50% from highs. 6

Treasury inflation protected securities are bonds that have a built in inflationary adjustment and should be a great way to track inflation, which is true, but the challenge with these is that the market mechanism for which inflationary expectations get priced in have been shown to be less accurate in the short term than assuming that inflation stays constant year over year. 7

Our View On the Best Way

So what does work? Our view is that owning stocks is the best way to tap into global growth and be a part of the economic engine that participates in increasing prices of goods and services. Stocks are not an inflationary hedge, rather they outperform inflation over time, allowing your wealth to increase in purchasing power.

Shorter term government bonds have historically been a reliable hedge against inflation. They’re not an exciting story with incredible upside, but they offer principal protection without locking in a long-term yield so you can benefit if

rates increase.

Lastly, looking outside of the portfolio and into solutions in other parts of your financial life can be incredibly valuable. One example is the strategic utilization of debt. It can be a great tool and potentially allow you to borrow money at rates much lower than inflation over time. Another could be prepayment of known future liabilities. Although there can be opportunity costs of prepaying, locking in today’s prices for large purchases or expenses may be a great decision if future costs are much higher.

Unfortunately, there is no magic bullet to protect against high levels of inflation, and there is no surefire way to forecast its arrival, but that doesn’t mean that we can’t build an all-weather portfolio to mitigate its impact if, or when, it comes.

- https://www.independent.org/news/article.asp?id=2973

- https://www.ft.com/content/f12c2178-1cef-11e0-8c86-00144feab49a

- https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB124458888993599879

- FRED Economic Data – Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis

- JP Morgan Guide to the Markets, June 30, 2021

- https://tradingeconomics.com/commodity/lumber

- https://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/publications/economic-letter/2015/september/market-based-inflation-forecasting-and-alternative-methods/

NOTE: The information provided in this article is intended for clients of Carlson Capital Management. We recommend that individuals consult with a professional adviser familiar with their particular situation for advice concerning specific investment, accounting, tax, and legal matters before taking any action.